Pure Salmon has global ambitions, social impact aspirations

The Kingdom of Lesotho, a tiny country of great natural beauty entirely enclaved within South Africa, is not particularly known for its fish.

Formerly known as Basutoland – the sovereign state declared independence from British colonial rule in 1966 – its traditional cuisine features dishes like oxtail soup and corn-based porridges. But one Singapore-based company aims to make this nation of 2 million people known for a local fish that’s truly anything but local: Atlantic salmon.

“If you go to your local sandwich shop or sushi restaurant, that fish has probably been flown in from Norway,” said Martin Fothergill, one of three founders of global asset management firm 8F, founded three years ago and now boasting satellite offices in London and Tokyo. Fothergill and his partners Stephane Farouze and Karim Ghannam say that salmon can be grown anywhere, with the right team and technology. Both will be in place in Lesotho, he told The Advocate, several hundred kilometersfrom the nearest ocean. Their company, Pure Salmon, announced plans last month to create a land-based reticulating aquaculture system (RAS) that will perch up high in the nation’s mountains.

“If you’re in South Africa eating fresh salmon from Lesotho, it’s going to be much fresher than fish imported from Norway,” Fothergill said.

From finance to farming

The three partners worked together at Deutsche Bank for many years before striking out on their own. Fothergill, who heads up the UK and Europe divisions, has more than 24 years’ experience in the finance industry and said the firm is focused entirely on aquaculture impact investments. Last year, it launched Pure Salmon.

“Pure Salmon is the global operating company and it provides services to all our land-based facilities,” he said. “It will oversee the operations in Lesotho, which will have its own complete staff on the ground. We’re completely dedicated to this area of the industry and have numerous projects in various stages of development around the world.”

Its first RAS facility, in Poland, is already operational and selling market-size fish of 5 to 6 kg. It will hit full commercial capacity by the end of October. Ground will also be broken in Japan on a new project with a 10,000-metric-ton (MT) capacity before the end of the year. Soul of Japan, as it will be known, will be completed by 2021, but it has already secured a major distribution partner. The retail value of the deal is an estimated $200 million (U.S.) per year.

Yet another facility of 10,000-ton will be built in Europe, either in France or Italy, as well as an additional 20,000-MT facility in the eastern United States.

“It’s a very ambitious project,” said Fothergill. “We’re rolling out a 260,000-ton global land-based salmon production, which is an extremely major development in the salmon farming industry.”

Pure Salmon has partnered with AquaMaof, an Israeli company specializing in aquaculture technology that holds a 50 percent share in the Poland project. This facility is a prototype for the company’s expansion around the globe, and is used for research and development, as well as training staff.

The same technology will be used in Lesotho. The land-based tanks offer a contained and controlled system for growing fish that closely mimics the natural environment. Water is kept clean by constant re-circulation, re-oxygenation, and filtration, and temperature is maintained at optimum levels.

“It takes about 20 months from first feeding to grow a market-size salmon in our system,” said Fothergill. “They are essentially the same as the fish farmed at sea – with similar color and taste. However, they tend to have firmer texture, more like wild salmon, because they get a lot of exercise in the tanks.”

The technology has many benefits. The risk of disease and contamination is reduced, and productivity is more efficient.

Our efforts on this project go above and beyond just building the facility. We really are focusing on the impact we can have on the economy and the local population.

Harvests can be planned and production costs are 40 percent lower than traditional sea-cage farming, said Fothergill. The $250 million Lesotho facility will be completed by 2023.

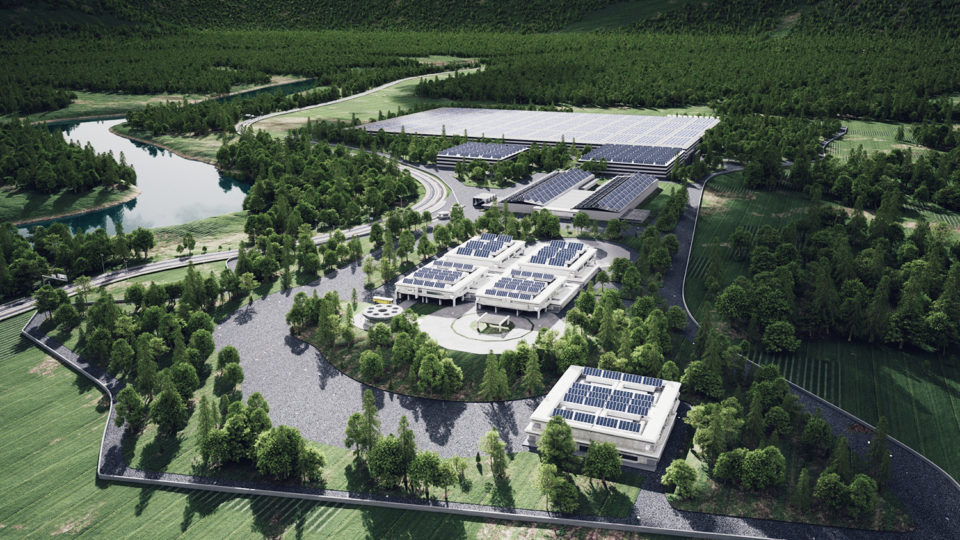

“It’s a fully integrated facility, as all our new facilities are,” he said. “That means a hatchery, nursery and grow-outs, as well as processing, smoking, packaging and distribution – everything – all in one site, which is very different to how the traditional fish farming industry typically works.”

While farming in the sea comes with challenges like parasites, diseases, algal blooms and micro-plastics, farming in land-based tanks presents less risk.

“You’re also not damaging the sea,” said Fothergill. “You’re not putting antibiotics into the sea. You’re not mixing farmed salmon with wild salmon, and you’re not susceptible to the risks of rising sea temperatures, or bad weather, or escapes – or anything like that.”

The facility will be in the Butha-Buthe Highland region. At more than 2,000 meters above sea level, summers there are fairly mild, but winters get cold, with mountain peaks frequently capped in snow. The high altitude creates perfect conditions for pure, uncontaminated water, and a nearby hydroelectric power station will provide clean energy.

Such facilities can be installed just about anywhere geographically, Fothergill argued, which would cut down on carbon emissions from transportation. There is less waste and because they lie closer to their final destination – the consumer’s plate – they are fresher and have a longer shelf-life – all making the idea of locally grown sushi products a reality.

Neighboring South Africa’s influence

The Lesotho project is however slightly different to Pure Salmon’s other global ventures.

“Typically, we’re looking for areas of existing high salmon consumption, so that’s why places like Japan and the United States are natural choices,” he said. “But we also wanted to have a project that could provide salmon to Africa. We wanted to have a deeper investment impact.”

Pure Salmon will be selling their fish regionally as premium products, with South Africa a key market, said Fothergill, adding that in time the company will “have the ability to export further afield.”

Fothergill estimates the project will generate annual revenues of about 8 percent of Lesotho’s GDP. This figure is significant by any standard, but it’s especially significant when one considers that the Lesotho government spends about 9 percent of its GDP on welfare programs, according to a 2018 report from the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Many of the country’s citizens live in poverty. The World Bank found that while Lesotho’s headcount poverty rate ($1.90/day of purchasing power parity, or PPP) has steadily reduced, 2018 estimates show that 53.7 percent of the population is still “trapped under the $1.90 poverty line.”

The project’s contribution to the economy will therefore be considerable, given the jobs it will create. Pure Salmon has partnered with the Lesotho National Development Corporation (LNDC), a government institution tasked with attracting investment and growing the economy. The project will create over 250 permanent jobs, and a foundation has been set up to support local communities. The company is offering aquaculture scholarships and internships, and local communities will also receive direct ownership shares for the use of their land. One million meals per year will be donated to schoolchildren and orphans during the first decade of operations.

According to a 2018 report issued by the Southern African Development Community (SADC), Lesotho’s annual per capita fish consumption is 0.8 kg. The aquaculture sector produced a mere 1,300 MT of fish in 2016 and accounted for about 0.15 percent of the country’s GDP.

“Our efforts on this project go above and beyond just building the facility,” said Fothergill. “We really are focusing on the impact we can have on the economy and the local population.”

With such figures and a corollary commitment, the prospects of this new project indeed seem promising – not only for Pure Salmon, but also the people of Lesotho.

Follow the Advocate on Twitter @GAA_Advocate

Now that you've reached the end of the article ...

… please consider supporting GSA’s mission to advance responsible seafood practices through education, advocacy and third-party assurances. The Advocate aims to document the evolution of responsible seafood practices and share the expansive knowledge of our vast network of contributors.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Author

-

Marie-Louise Antoni

Marie-Louise Antoni is a freelance journalist based just outside of Cape Town, South Africa. She has written on crime, politics, law, media matters and the environment.

Tagged With

Related Posts

Innovation & Investment

Is RAS the game-changer that Europe’s aquaculture sector needs?

The impact that recirculating aquaculture systems, or RAS, will have on European production remains to be seen, but the general vibe is positive.

Intelligence

RAS in the USA: Fad or future?

A rash of large-scale, land-based recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS) are planting their flags on U.S. soil, even though it will take several years and hundreds of millions of dollars of investment before they produce their first sellable fish.

Innovation & Investment

Israeli firm’s ‘plug-and-play’ RAS solution attracts investment

BioFishency's two products, the Single Pass BioFilter and the Mini-RAS, each aim to improve the survival, growth and reproduction rates of fish, which increases profitability and sustainability for the farmer.

Responsibility

In South Africa, abalone farming goes for gold

Poaching has plagued South Africa’s abalone to the point of decimation. Aquaculture is putting the shellfish back in the water, and back on menus.