Stone family brings Midwest ‘agricultural spirit’ to one of Florida’s newest shellfish farms

Gretchen Stone had just started raising clams when she made a big mistake: She and her brother, Ian, were in their boat, pulling up mesh bags from their 30-acre lease in the Suwannee Sound and rinsing off the mud when another clam grower stopped them.

“We were washing [the clams] out over the top of our lease and onto the bags we had planted below,” Gretchen recalls. “[The grower] said, ‘The mud will suffocate those clams [growing below] and you’ll have bad product in a year. It’s something that would never impact him and he stepped out of his way to help.”

The interaction was important to the Stones, who arrived in Cedar Key, Florida, USA, with no experience farming clams and no ties to the tight-knit rural fishing community. The pair worried that longtime residents and experienced clam farmers might not welcome newcomers.

“It was intimidating, to say the least, but we quickly realized how helpful and generous people are in Cedar Key,” Gretchen told the Advocate. “We’ve had nothing but love and support and help.”

The small island community of Cedar Key itself received help back in the 1990s to launch a shellfish aquaculture industry off the Gulf Coast of Florida. When regulatory closures and restrictions decimated the local fishing industry, federal retraining dollars were allocated to teach fishermen about aquaculture. The funds covered classroom instruction and permitting, surveying and marking submerged land and granting program graduates leases to begin raising shellfish.

Cedar Key fast became the No. 1 farmed clam region in the state with 150 certified growers managing 900 acres of submerged lands dedicated to aquaculture leases. Clams are the top product.

“In Levy County, around 70 percent of our coastline is tied up in public trusts like wildlife refuges or state preserves,” explained Leslie Sturmer, shellfish aquaculture extension specialist with the University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. “We have good lease sites, good growing conditions so [clam aquaculture] works; it works very well.”

Focused on farming

Until 2018, Gretchen and Ian had never seen a clam farm or heard of Cedar Key, Florida.

The fifth-generation farmers from Kansas had planned to continue the tradition of growing corn, wheat, soybeans and alfalfa and raising cattle in the Midwest. But the aquifer that served as their main source of water was being pumped dry, margins were getting slimmer and their futures on the farm felt increasingly tenuous.

When their father, Greg Stone, suggested the pair trade their cowboy boots for rubber boots to start a clam farm, it piqued their interest.

“We always had the desire to be full-time farmers but there was no job for us on our family farm when we got out of college,” Gretchen said. “[Aquaculture] provided the opportunity for us to get into farming, run our own business and enjoy the fruits of our labor.”

Greg Stone hoped to establish an aquaculture operation in the Midwest where the family had farmed for generations, but his plan was flawed.

“We were talking about growing algae, then clams and oysters, in Kansas,” Ian recalls. “We would have needed to pump [an incredible amount of water] and wouldn’t have been able to produce enough food for the shellfish. It just wasn’t feasible to do in the middle of nowhere.”

Greg Stone refused to give up on aquaculture so, when he saw an ad offering a clam farm for sale in Cedar Key, he convinced his children to swap corn for clams. Gretchen and Ian gave up their jobs in the food sciences and biofuels industries and moved to the Sunshine State.

All in on aquaculture

Rather than starting small, the pair went all in. Their operation, Big Moon Sea Farm, includes a 10-year lease on a 30-acre parcel in Suwannee Sound. A background in conventional agriculture has proven helpful but the Stones also see gaps in resources that could boost productivity and improve efficiency, making them more successful growers.

“At this stage, we’ve tried to think about clam aquaculture like a terrestrial farming practice,” Ian says. “The industry in Cedar Key is only 25 years old so it’s still in its infancy but with corn and cattle, we’ve had centuries to figure it out.”

Their biggest roadblock: Lack of access to data.

Gretchen and Ian wanted a better method to track their planting records. They sought out Chip Terry, CEO and founder of OysterTracker, a shellfish aquaculture management platform designed for oyster growers, and asked him to adapt the tool for clams. Gathering data about baskets, rows and yields – just as they did when raising row crops in Kansas – helped the new clam growers track production and measure the quality of seed from the hatcheries.

“It’s been awesome but it’s just the beginning,” Gretchen said. “There are a hundred other things that we’d like to improve in the next two years.”

A commitment to learning everything they can about farming clams and a desire to improve their farm and the aquaculture industry has helped Gretchen and Ian build a thriving business and find a home in Cedar Key.

“These have always been small, isolated rural communities, and we don’t have a lot of new people coming in,” Sturmer says. “[Gretchen and Ian] are atypical because they moved here and had no prior clamming experience, but they have become well accepted in this community.”

Ian credits a shared passion for farming as the main reason that moving across the country and transitioning from agriculture to aquaculture has been a success.

“There is the same agricultural spirit [in Florida] that we saw in Kansas,” Ian said. “Whether it’s corn or cattle or clams, at the end of the day, farmers are honest, hardworking people who want to be good stewards of the land.”

Follow the Advocate on Twitter @GAA_Advocate

Now that you've reached the end of the article ...

… please consider supporting GSA’s mission to advance responsible seafood practices through education, advocacy and third-party assurances. The Advocate aims to document the evolution of responsible seafood practices and share the expansive knowledge of our vast network of contributors.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Author

-

Jodi Helmer

Jodi Helmer is a North Carolina-based journalist covering the business of food and farming.

Tagged With

Related Posts

Innovation & Investment

Tuna aquaculture: Fishing for progress

Aquaculture could be a sustainable alternative to fishing for tuna but achieving commercial-scale production has proven challenging.

Innovation & Investment

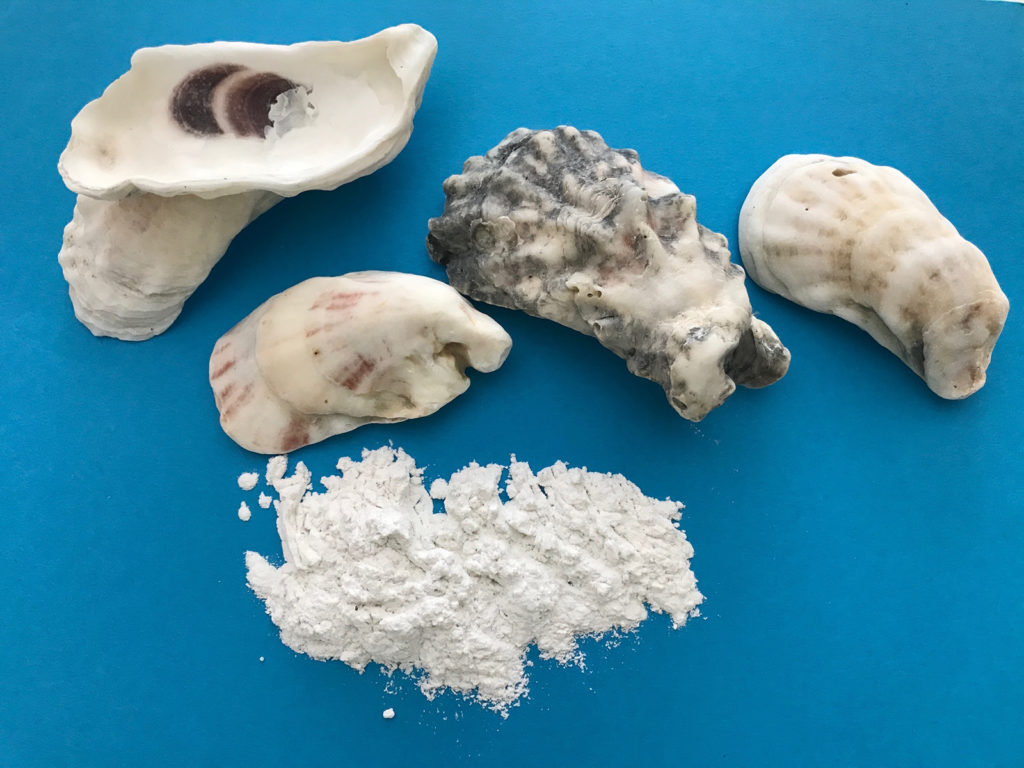

Can an oyster-shell paint help rethink artificial reefs?

North Carolina company Shellbond seeks to commercialize a creative product made from shells, believing it could transform oyster farming.

Aquafeeds

Wood you believe it – a fish feed ingredient from the forest?

Arbiom hopes to ride the wave of interest in novel feed ingredients and expand production of a nutrient-rich protein meal made from wood residues.

Innovation & Investment

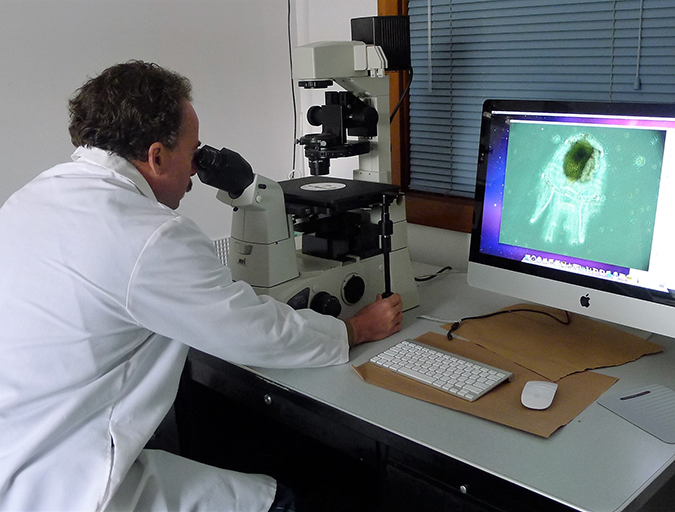

Better together: Partnerships drive innovation at leading labs

Laboratories with industry partnerships are making aquaculture more innovative, efficient and responsible. These collaborations offer access to expertise, facilities and funding to further the industry and improve global food security.