SCORE aimed to determine how different diets influenced weaning success

The winter flounder, Pseudopleuronectes americanus, is one of the thickest and meatiest of all the flatfish in the northeastern United States. Although the fish supports valuable commercial and recreational fisheries throughout its range, coastal populations have steadily declined over the past 30 years. For example, in 1982, commercial landings in the Gulf of Maine amounted to approximately 3,000 metric tons (MT), but this dwindled to 260 MT by 2007.

Individual marine fish are capable of releasing over 100,000 eggs annually, but because of the vulnerability of the small, early life stages, few survive to maturity. Spawning and rearing flatfish in captivity, and releasing the young at an age beyond this period of high mortality could enhance natural populations.

Stock enhancement is one of the few tools available to fisheries scientists and managers for stabilizing, conserving and restoring natural stocks. The Science Consortium for Ocean Replenishment (SCORE), of which the University of New Hampshire is a part, is examining winter flounder as a potential stock enhancement candidate.

Diet, weaning challenges

A major challenge for any captive-rearing program is providing the appropriate diet regimes during development. Typically, cultured marine fish larvae are initially fed live food such as rotifers and artemia, then weaned onto formulated diets as they attain a size or developmental state that supports consumption of the artificial feeds.

Weaning onto formulated diets is a stressful time for cultured fish, especially flatfish that have just undergone the dramatic morphological and physiological transformations associated with metamorphosis. Once released, fish reared for stock enhancement must also transition from formulated hatchery feed back onto live diets.

Fish can take several days to begin feeding on wild prey, and even then, nontraditional food sources may be selected because of size or shape resemblances to formulated diets. This short period of starvation during the wild transition also can alter feeding behavior and result in an increased predation risk for reared fish. Thus, maximizing the success of both hatchery and wild weaning is paramount for any applied stock enhancement effort.

SCORE study

The overall objective for the SCORE team was to quantify the weaning success of reared, then released winter flounder juveniles. Researchers aimed to determine how different live and formulated diets influenced weaning success in the hatchery, as indicated by growth and survival. They also planned to evaluate how this success translated to the weaning of individuals to wild prey once the fish were released into nature by examining growth, survival, gut fullness, diet composition and RNA/DNA condition. The latter three components are currently being analyzed.

The field season began in March 2008 with the capture of broodstock from a local commercial fisherman and culminated in October with retrieval of the last cage of released fish. Fish-rearing and hatchery feeding trials were performed at the University of New Hampshire Coastal Marine Laboratory in New Castle, New Hampshire, USA. Cage trials were conducted in an adjacent cove at the mouth of the Great Bay Estuary.

Hatchery feeding trials

The hatchery feeds examined included two traditional feeds: a 0.5- to 0.8-mm pelleted feed with 60 percent protein, 15 percent lipid and 10 percent ash; and artemia brine shrimp with 55 percent protein and 35 percent ash grown out on Spirulina to subadult stages. The two nontraditional feeds were white worms (Enchytraeus albidus), a natural component of the winter flounder diet with 75 percent protein and 15 percent lipid; and burying marine amphipods (Leptochierus plumosus), another item in the natural flounder diet with 55 percent protein and 35 percent ash.

Live feeds were chosen because of their rearing and harvesting ease, their tendency to thrive with minimal maintenance and their ability to survive in saltwater and brackish water for prolonged periods.

To examine weaning success, the authors established a randomized block design using three large rectangular trays with two flow-through tanks per diet type. Each tank housed 12 individual fish with a standard length of about 30 mm. Trials were conducted for four weeks with a subset of four fish from each tank measured weekly for total length, standard length and weight.

Mortalities were removed daily, and the temperature, dissolved-oxygen and salinity values of each tank were measured daily. Although the tanks were nestled in a flow-through system, each was siphoned twice weekly or whenever dissolved-oxygen levels dropped below 5 mg per liter. The fish were fed three times per day at a level of approximately 15 percent fish body weight.

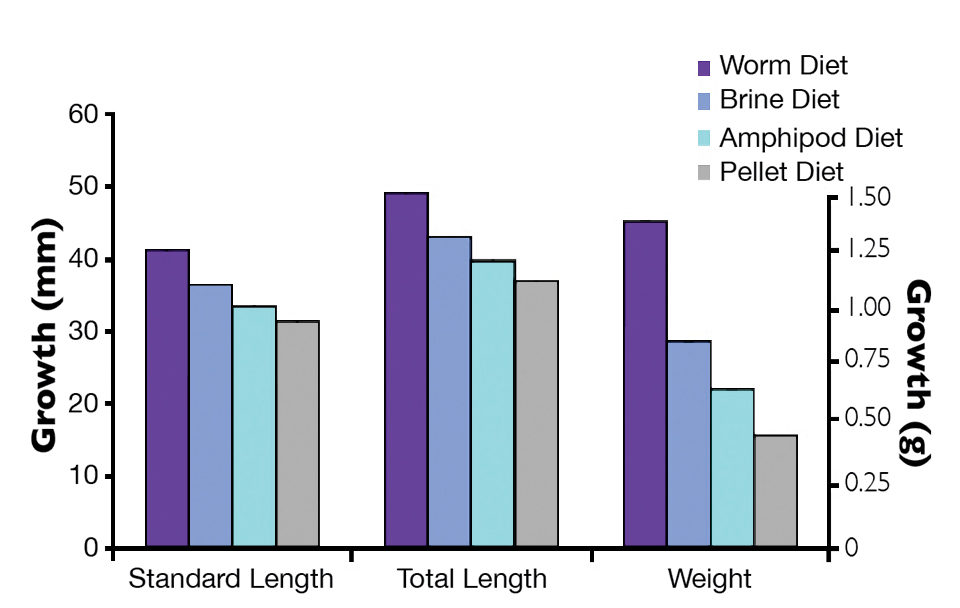

In terms of survival, there was no large difference in survival among the three live feed-reared fish tested. However, pellet-reared fish showed marked mortality. Approximately half of these fish died during the course of the trials, with the majority in the final two weeks. Fish reared on white worms grew significantly more for all three measures, followed by those that received brine shrimp, amphipods and pellets (Fig. 1).

Cage growout trials

The surviving fish from the hatchery trials were used for the wild cage releases. During the two-day transition between trials, the cultured fish were tagged by color code for feed type. Wild fish were also captured in the cove. The wild fish had a mean total length of 73 ± 8 mm, and so were much larger than the lab-reared fish at 42 ± 4 mm.

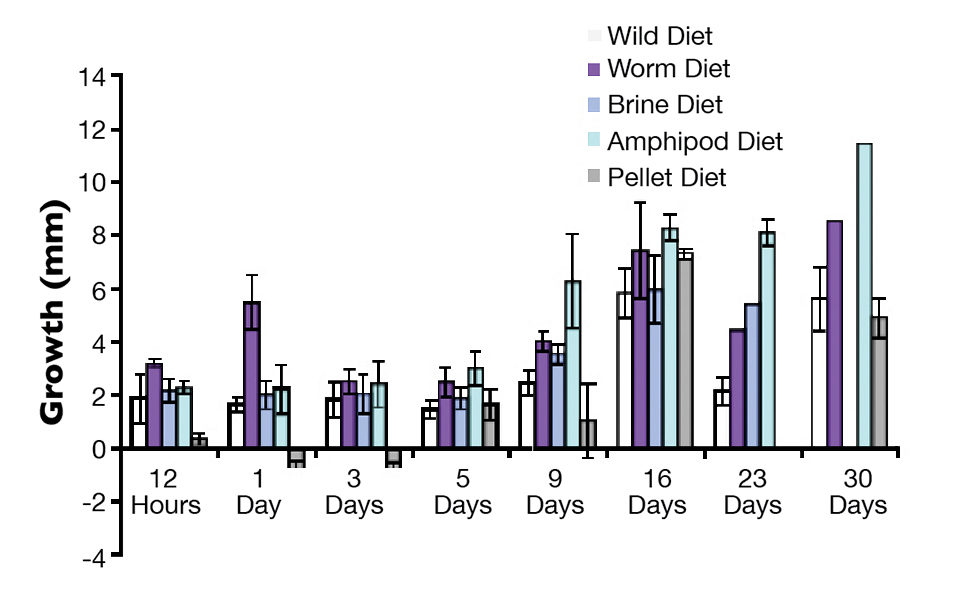

The flounder were released in 52- x 38- x 20-cm cages nestled into larger, heavier cages to stabilize them in the mud and provide an additional barrier against encroaching predators. Each cage received 15 fish, three of each feed type plus three wild fish. The cages were retrieved between 12 hours and 30 days postrelease in eight cage-hauling events.

There was no large difference in survival among the cage-released fish reared on any of the feed types. When analyzing wild weaning success by growth, the white worm-reared fish again exhibited some of the highest growth (Fig. 2). However, fish reared on amphipods grew the most of all. Given that the amphipods were a livelier, more challenging feed, the fish that consumed them may also have gained better training for the life of an active predator in the wild than those fish reared on other feed types.

Further success

To promote further flatfish stock enhancement weaning success, scientists must continue to identify nutritious, inexpensive live hatchery diets that can be easily mass cultured. Pellet-reared fish may need to be trained more effectively to become successful predators. Additionally, reducing and/or phasing out the use of pellets altogether when rearing winter flounder for stock enhancement may be considered.

(Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the May/June 2009 print edition of the Global Aquaculture Advocate.)

Now that you've reached the end of the article ...

… please consider supporting GSA’s mission to advance responsible seafood practices through education, advocacy and third-party assurances. The Advocate aims to document the evolution of responsible seafood practices and share the expansive knowledge of our vast network of contributors.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Authors

-

Michelle L. Walsh

University of New Hampshire

Spaulding Hall

38 Academic Way

Durham, New Hampshire 03824 USA[117,100,101,46,104,110,117,64,104,115,108,97,119,46,101,108,108,101,104,99,105,109]

-

Elizabeth A. Fairchild

University of New Hampshire

Spaulding Hall

38 Academic Way

Durham, New Hampshire 03824 USA -

Nathan Rennels

University of New Hampshire

Spaulding Hall

38 Academic Way

Durham, New Hampshire 03824 USA -

Stacy C. Farina

University of New Hampshire

Spaulding Hall

38 Academic Way

Durham, New Hampshire 03824 USA -

W. Huntting Howell

University of New Hampshire

Spaulding Hall

38 Academic Way

Durham, New Hampshire 03824 USA -

Renee Mercaldo-Allen

Catherine Kuropat

Northeast Fisheries Science Center

Milford, Connecticut, USA

Tagged With

Related Posts

Health & Welfare

Dietary organic acids improve gut health, disease resistance in olive flounder

A study evaluated the effects of two organic acid blends on performance, gut health and disease resistance in olive flounder. The dietary organic acids were effective in lowering total gut bacterial counts, gut Vibrio counts and in conferring resistance against Edwardsiella tarda.

Health & Welfare

Korean researchers study protein levels, P:E ratios in olive flounder diets

The authors conducted research to determine the optimum dietary protein levels and protein:energy ratios for different age groups of olive flounders.

Intelligence

Bahamas venture focuses on grouper, other high-value marine fish

A new venture under development in the Bahamas will capitalize on Tropic Seafood’s established logistics and infrastructure to diversify its operations from processing and selling wild fisheries products to include the culture of grouper and other marine fish.

Intelligence

A brief look at genetically modified salmon

If approved by FDA, fast-growing genetically modified salmon will provide a safe and nutritious product similar to other farmed Atlantic salmon.