Built on a dream of feeding some of the world’s poorest and most vulnerable people, a charity-built tilapia hatchery in Haiti now learns to stand on its own

Why in the hell is there no aquaculture on this island?

Part I – The mission

After arriving in Haiti for the first time about a decade ago, Bill Horan wondered why the people who lived there seemingly didn’t eat any fish. He’d ask them why and the answer was always the same – the fish are all gone. Which seemed odd to him, given that the sunny island is dotted with pristine lakes and surrounded by the Caribbean Sea.

As the head of a faith-based humanitarian disaster-relief organization, Horan’s charge was eradicating hunger, with an eye on long-term solutions. His work has taken him to some of the most poverty-stricken areas of the world. Haiti is, according to the World Bank, the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere, capable of producing less than half of the food its people require. The natural waterways and man-made reservoirs throughout Haiti’s rugged countryside, he would soon learn, had been essentially “strip-mined” of their native fish. Generations of starving people had few other options but to forage for even the tiniest fishes, their land’s ability to provide critically impaired by deforestation, pollution and decades of political turmoil.

After the devastating 2010 earthquake that killed hundreds of thousands of Haitians and displaced more than 1 million others from their homes, particularly in and around the capital city of Port-au-Prince, humanitarian organizations that responded were met with unprecedented challenges. To have a positive impact here, they’d have to overcome, among many other things, predominant perceptions about the country, about its people and about working there – concerns that existed long before the disaster.

“Frankly, I had a bad attitude about it. I had bought a bit into the misinformation. That it was violent. That the people were lazy. It’s just not true,” Horan says. “Haitian people are wonderful, and hard-working. They are family-oriented, very spiritual, good people. But much maligned.”

Horan, now 75, retired nearly a year ago but frequently speaks of his 16-year career with Operation Blessing International Relief and Development Corporation in the present tense. That’s because the work he carried out as its president remains his passion: feeding the hungry. And, as he describes, there remain many hungry people in Haiti: “A lot of people do not have good food to eat. Rice and beans, occasionally a chicken. There’s virtually no protein in their diet, so you see all of the problems – stunted growth, rickets, the physical manifestations of not having a nutritious diet.”

The typical hunger-relief model – coordinating shipments from corporate donors and trucking them to distribution centers, all with a mainly volunteer work force – would not work for Haiti, Horan determined, due to high costs, unreliable infrastructure and unpredictable (and often arbitrary) customs delays. To truly fulfill the mission of Operation Blessing, a nonprofit Christian humanitarian organization, would be to find a lasting fix to food insecurity, while limiting imports of goods and services.

“We’re looking for innovative ways to feed people, or better yet, to get them to feed themselves,” explains Horan, who said that Operation Blessing originally went to Haiti to install a safe-water system at a rural hospital run by prominent nonprofit organization Zanmi Lasante, but later expanded its mission after witnessing such a great need for nutrition. (Zanmi Lesante is the sister organization of Boston-based Partners In Health.)

“That saying, ‘teach a man to fish’ – it’s a good one,” he says.

If only there were fish. Horan tried aquaponics, which he liked in theory because a simple system could produce fish in addition to vegetables. But he determined backyard gardening kits, no matter how sophisticated or simple, could not make the necessary impact: “I thought, ‘Why in the hell is there no aquaculture on this island? The answer was nobody knows what they’re doing. Churches and missionaries had tried. They built little ponds, threw some fish in there. But if you don’t understand water chemistry and biology, it soon goes belly up.”

I don’t want to write checks. I want to leave businesses that are economically sustainable.

Part II – The builder

Mike Picchietti has practiced aquaculture all over the world. Over nearly four decades in tilapia farming – half of that spent with leading producer Regal Springs until his retirement in 2011– he built fish hatcheries and grow-out farms in Brazil, Africa, Central America and Southeast Asia. Many of those facilities remain in operation, producing thousands of tons of frozen tilapia fillets every year that are shipped to major U.S. retailers like Costco and Kroger, via sales channels he helped to establish. Regal Springs is one of the biggest players in the global tilapia industry, with Picchietti one of its architects.

He still runs his own business, Aquasafra, a tilapia hatchery in Bradenton, Fla. At first glance it looks like a nondescript network of greenhouses, but underneath the series of translucent tarpaulin roofs some 6 million juvenile tilapias – known as fingerlings – are produced each year and sold to farming operations that grow them to market size. He’s been running this facility since 1992 and owns and lives on the property with his wife, Brenda.

If all his years in aquaculture taught Picchietti anything, it’s that the hatchery – or at least reliable access to high-quality seed – is perhaps the most crucial aspect of a fish-farming business, particularly a new one. Sales and seed, he says, are highly interconnected and a failure to deliver on either one brings “direct and immediate” impacts. In Regal Springs’ early days, whenever there were troubles with the business, it usually had something to do with the hatchery.

In 2011, a few months before Picchietti would eventually sell his interest in Regal Springs to his partners, he attended a World Aquaculture Society conference in New Orleans, La., where William Mebane of the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Mass., spoke about rudimentary tilapia ponds that had been constructed in a rural part of Haiti. (In a similar TED presentation posted on YouTube, in which Mebane reflects on his eight years of work in Haiti, he described the land as “a lot like the moon. You can barely hammer a nail into the soil.”)

At the end of his talk, Mebane invited the leader of a charity exploring fish farming in Haiti, albeit on a larger scale, to introduce himself and appeal for advice or assistance from what was a highly technical and largely academic audience. Picchietti, who did a stint in the Peace Corps on catfish farms in Africa as a younger man, was in the room. He had been wanting to return to charitable work in his retirement and a “reverse Peace Corps” type of arrangement, as he describes it, held some appeal. The next day he sought out that speaker and introduced himself to Bill Horan.

“We talked for an hour, quite intensely,” Horan says of the initial encounter. “He was involved with tilapia for many years and was selling his interest in a company. He said to me, ‘I’ve been feeding people at the top of the pyramid all of my career. I want to go back to where I started.’”

But Picchietti didn’t want a consulting role. He wanted to be involved with operations, from the ground up. He wasn’t afraid to get hands wet, as they say in the fish farming business.

“I don’t really believe in consulting. It’s not really helpful to have an expert come for two weeks and leave if it doesn’t work. You have to go and put your feet down and work it,” Picchietti says. “I was thinking about going back to Africa. I want to help the poor with food. I don’t want to write checks. I want to leave businesses that are economically sustainable.”

Picchietti also told Horan that a working arrangement might not be a perfect fit after all. As Horan explains, Picchietti wasn’t very fond of non-governmental organizations, or NGOs, either: “‘They just talk and spin their wheels,’ he said to me, ‘but I think we can get along.’ I thought, holy cow. But he clearly knew what he was talking about. We had good personal chemistry. Two grumpy old men. We clicked.”

I needed to go into aquaculture in a much bigger way if I was to make a dent in the hunger in Haiti.

Part III – The blueprint

A few months after their first encounter, Horan went to Florida to visit Aquasafra, where he saw thousands of baby fish, from carefully selected breeding lines, thriving in a bio-secure environment. It “blew my mind,” he says, and he knew instantly that if they could build something just like it in Haiti, his crazy dream might become reality.

Horan had been fascinated by fish as a teenager, although he never pursued a career in aquaculture. His family property in Michigan sat on an ancient gravel deposit that contained several aquifer-fed ponds, which he would stock with fish that he caught, like perch and smallmouth bass. He stocked one pond with fathead minnows and within a couple of months, “you could walk on the water” there were so many fish in there.

“That saying about Jesus feeding the multitudes with fish? They must have been fathead minnows. They were reproducing like crazy,” he says with likely the same level of excitement some six decades later.

It was fish that connected Horan to Operation Blessing in the first place. He was living six months a year on Grand Cayman when the vacationing media mogul and televangelist (and Operation Blessing founder) Pat Robertson tracked him down for a fishing trip after learning Horan was president of the Cayman Islands Angling Club. “We met, and we hit it off,” says Horan. “[Eventually], he asked me to run this global humanitarian charity, and grow it. I thought he had me mixed up with someone else. As bizarre as it sounded, I thought I’d give him a couple years. I was there for 16.”

Horan’s interest in fish farming never waned as he got older, and in the early days of Operation Blessing’s efforts in Haiti, he bought an advanced aquaponics kit and had it shipped to Haiti. He got a great deal on it, but it just wasn’t the right fit. That’s because, in his mind, it wasn’t really aquaculture – it was way too small.

“I found out that aquaponics is much more about the vegetables than the fish,” he says. “I needed to go into aquaculture in a much bigger way if I was to make a dent in the hunger in Haiti.”

Knowing what a viable hatchery actually looked like, and with a capable technical partner in Picchietti, who had signed on as a subcontractor, Operation Blessing set out to build something similar to Aquasafra in Haiti. Picchietti, who would eventually spend a week in Haiti every month for several years until the hatchery was running smoothly, even donated 60,000 fingerlings to kickstart the operations. It was the beginning of what Horan describes as a “very exciting ride, filled with peril and all sorts of obstacles.”

“We weren’t going to teach a man to fish – we were going to teach a whole country how to farm fish!” Horan says, recalling their tenacity at the outset. “Most would say it couldn’t be done. We wanted to prove that it could, and could be done right. I like to think we did it the right way, with meticulous standards, as if we were raising fish for the U.S. market.”

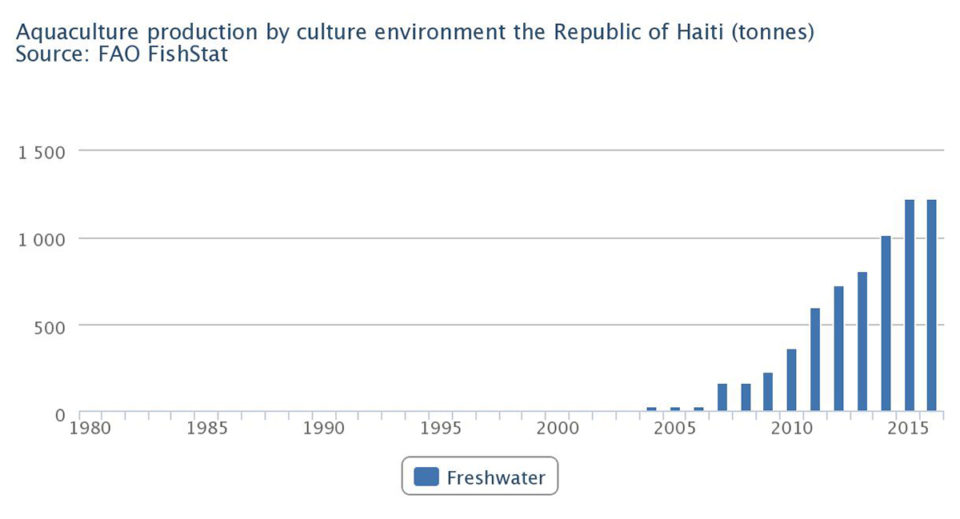

In June 2011, Picchietti visited Haiti for the first time and by that October a Haiti-scale version of his Florida hatchery was under construction in Santo, east of Port-au-Prince. It started out producing fingerlings to stock in area ponds and reservoirs with the aim of establishing fisheries. In January, fish were put in the water and by the end of 2012, they had enough fish to open up a small restaurant.

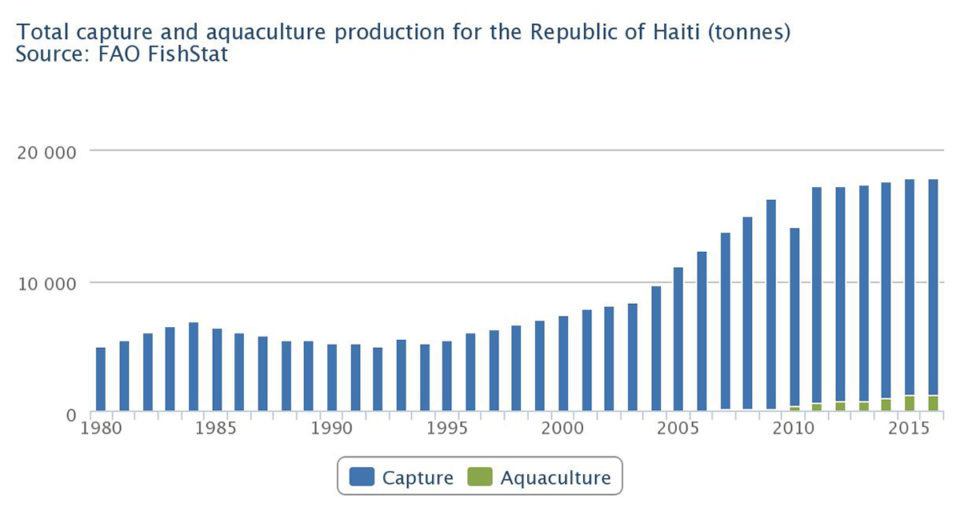

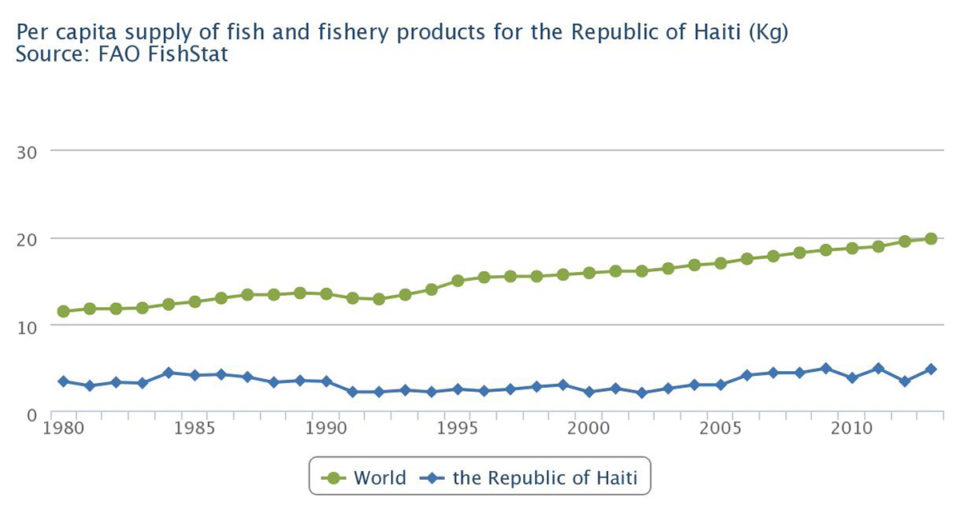

“We started a cage farm and hired some guys from Regal. Five years later [we realized] the hatchery actually had some traction. If there’s any place that could use it,” Picchetti says. “The potential is there – 10 million people, they import 80 percent of their food and have the lowest fish consumption, per capita, in the Caribbean.”

Nobody needs this fish more than the residents of Zanmi Beni, a dormitory on the outskirts of Port-au-Prince that Zanmi Lesante (which in Haitian Creole loosely translates to “friend in health”) built for children with disabilities, many of them abandoned or orphaned after the earthquake. Horan gets emotional when he speaks of the 54 full-time residents there: Feeding these children, among the most vulnerable in Haiti, is mission-critical.

“They eat the fish two to three nights a week. They’d eat it every night if we had enough! They love it,” he says.

Eventually Operation Blessing expanded the hatchery side of its operations, selling fingerlings to area producers. Horan’s and Picchietti’s vision for the business was for it to be profitable, to employ people and to supply much-needed protein for the community. The commercial aspect of the project didn’t always sit easy with the board of directors at Operation Blessing, but in Horan’s opinion, establishing a sustainable business – not just a food supply – was crucial for long-term success.

“I’m an entrepreneurial humanitarian. In my heart, I’m an entrepreneur. But when I went to Operation Blessing, I simply converted the way I measure success from dollars on a spreadsheet to how effectively I leverage resources to get as much relief as possible to the people I’m trying to help,” he says. “Our donors were my stockholders and their ROI is reduced suffering.”

It’s roots, which are spreading in every direction.

Part IV – The native son and the father

During the technology boom in the late 1990s, 19-year-old Hans Woolley left Haiti for the United States to chase a dream career in tech. He unquestionably found it, and was eventually involved with, as he says, “a couple startups.” One was Evite, a leading online invitation and social planning website where he served as president during a major growth phase. He’s also a co-founder of Peloton Interactive, makers of popular luxury exercise equipment, where he remains a shareholder.

After the earthquake, Woolley felt a strong pull back home to Haiti. Haiti, he felt, needed him.

“It was really difficult to see – to see how precarious everything was, how much of a challenge we faced to move out of this unsustainable economic and social fabric that existed at the time,” he says. “It wasn’t working. There were no longer-term plans in place to improve quality of life, no fundamentals for people to be productive, successful and work their way out of poverty. I thought, how could I add value?”

Without the tech-savvy talent pool that he was accustomed to in the United States, and without the common resources he once took for granted like reliable Internet service and electricity, he disregarded any plans to start a technology-based company in Haiti. Instead, he researched examples of countries that went from “third [world] to second, in a reasonable amount of time.” He found many noteworthy examples – Taiwan, the Philippines, Singapore, Indonesia, and even Haiti’s neighbor on the island of Hispanola, the Dominican Republic.

“All of them managed to make a significant transition. Was it aid? Economic development? Natural resources? What was it? What drives them to make it out, and be normal? Because in many ways, that’s what Haiti is challenged with: normalcy,” he says.

There was one common thread in all of those places. “Tilapia kept coming up,” said Woolley. “In particular, Taiwan was early pioneer, and turned tilapia into a massive industry, which was a remarkable contributor to its evolution from agrarian-based society to a developed civilization.”

Woolley and his brother Patrick, along with their cousin Gilbert, started a pilot tilapia farm using the Operation Blessing fingerlings, and eventually decided they could make a go of it in aquaculture in the town Fond Parisien, on the shore of Lake Azuei. The lake has a salinity level of about 8 to 12 parts per thousand (the ocean is about 30 ppt), but is well suited for tilapia culture. The business they built, Taino Aqua Ferme, operates a network of grow-out cages and quickly became the biggest customer of the Operation Blessing hatchery, buying tens of thousands of fingerlings a month.

“We want to be responsible about how we farm and are very cautious with that. Luckily, we were one of the first and can set the right example. Frankly, that’s something we need to be mindful about,” he says.

Pat Tracy, chairman and recently retired CEO of Illinois-based food redistribution giant Dot Foods, is one of the company’s investors, having met Woolley through Bill Horan. His family business is heavily involved with hunger-relief efforts and he himself has what he calls a “personal” interest in Haiti’s recovery. Dot Foods donates product considered “not sellable” and distributes it to people in need, a model that could succeed for Haiti, he says, but because it lacks a sophisticated food distribution system, moving frozen product, which Dot Foods specializes in, it would be tricky.

“Hunger relief is difficult any place you do it,” he says.

The intersection of charity, technical know-how and entrepreneurial spirit that he’s seen in Haiti with Operation Blessing and Taino Aqua Ferme is nothing short of “divine intervention.”

“Hans is a good entrepreneur, a smart guy who speaks the language and knows the system. His heart is there,” he says. “It seemed like we were brought together for a purpose. I love Haiti and love the people there, but it’s a challenging place. They don’t have electricity, reliable utilities or sound infrastructure. Violence is a factor and was a huge obstacle early on.”

Few know the harsher side of Haiti better than Father Richard Frechette. Living there since 1987, when the American Catholic priest arrived for a mission, he sees suffering every day of his life.

In his 30 years in Haiti, Frechette has become so much more than a church pastor. As a handyman, he fixes everything that needs fixing. As the founder of St. Damien Pediatric Hospital, he provides medical services to the poorest and most vulnerable children in the country. He’s a fighter who’s stared down street gang members trying to steal from him. The unbearably difficult work provided by one of his charities, the St. Luke Foundation for Haiti, was featured in a gripping December 2017 New York Times feature, The Heroes of Burial Road.

When contacted by the Advocate, Frechette had been stuck in a road barricade for hours amid burning tires and a spate of violent protests of the government that all started with rising fuel taxes that few can afford. He still found time to discuss one of his most recently acquired skills: tilapia farming.

On the comparatively tranquil grounds of St. Damien Pediatric Hospital, Frechette maintains 12 tilapia ponds of various sizes, a system made possible because of the Operation Blessing hatchery, which eventually donated 150 breeding females. With Picchietti’s ongoing guidance, his little farm has a reliable seed source – a point that Picchietti drives home to all who work with him.

“We think it’s terrific,” Father Frechette says of his boutique fish farm. “It’s a protein source. It creates work. It’s good for nature, providing irrigation for the garden, trees and plants, which the bees in our 80 beehives love. Unfortunately, in this country, 80 percent are lucky to bring in $600 a year, which is the average income. Among that class – 80 percent of 10 million – there’s a lot of malnutrition and hunger. That’s way too much for us to deal with. We have our share of vulnerable young people in our schools and programs, so at least in our radar we can do something. But the problem is a rather large one.”

Frechette hopes that other fish farms can be established along riversides in rural areas, like how it’s often done in China and Southeast Asia. He’s fully on board with aquaculture and its potential: “It’s roots, which are spreading in every direction.”

I don’t need to fly 24 hours to find suffering. This is an hour from Miami.

Part V – The transition

When Horan retired from Operation Blessing in April 2018, he knew other changes would soon follow. The first thing the new management did, he says, was drastically reduce the Haiti budget and the hatchery was at the top of the list of things that could no longer be afforded. As Horan explains, its donors wanted to focus on other needy areas.

“I spent more time [in Haiti] than my board preferred. We have work in 30-something countries,” he says. “I just thought, I don’t need to fly 24 hours to find suffering. This is an hour from Miami.”

Insistent that the hatchery must endure, Operation Blessing donated it to Zanmi Beni, the hospital and dormitory for disabled children. Zanmi Beni leases it to Taino Aqua Ferme, run by the Woolley family.

“We wanted the kids to keep eating the fish they’d gotten used to,” says Horan, who wishes he were 20 years younger to help the hatchery grow and fulfill its promise. With friends like Zanmi Beni, Father Rick Frechette, Pat Tracy, Hans Woolley and Mike Picchietti, Horan is optimistic about the future of fish farming in Haiti.

“I’m not a stargazer, by any stretch,” he says. “But one of the things that could help here is aquaculture. Still, there’s no feed [source] on the island, you got to bring it in.”

That could spell trouble for existing aquaculture operations hoping to expand into something resembling an industry. While Haiti’s lagging import-export infrastructure can often lead to long delays and headaches for producers, Horan insists that one of the struggles he’s not encountered is government corruption, dispelling another myth about the country.

“It’s fair to say it’s an unstable government,” he says. “But in all my trips, I had no eyewitness proof of corruption. No one asked me for a bribe. Ever. The government people I dealt with over the years, without exception, were professional, intelligent, organized and devoted to what their authority encompassed. They want good things to happen in Haiti.”

Aquaculture is unquestionably one of those things, says Woolley.

“Aid isn’t the route to success; it’s got to be for-profit investment,” he says. “New industries, new jobs, new skillsets – they percolate to other sectors and ultimately you build critical mass over the tipping point, to self-sustaining economic development.”

Taino is succeeding because of its entrepreneurial nature, he adds: “We had a good beginning group of folks. We jumped in. We invested: a hatchery, a processing plant, a cage system on the lake, distribution, sales. It became a real startup, and I understand that world. We’ve struggled to achieve profitability, but we hope we can get there this year. Our goal is to build a company that can serve as a cornerstone for a real aquaculture industry, a platform that will enable others to jump in with investment. We need aquaculture.”

Building a business takes courage, but developing an industry in Haiti may very well require funding from overseas, says Picchietti, including private investors who see the upside and are patient for results. “I wouldn’t know what to do if it were easy,” he says.

As for Horan, he knows the little fish farm he’s called his “baby” for the past seven years must take the next steps on its own.

“I’m exceedingly proud,” says Horan. “I’m not supposed to use that word, as a Christian, but I’m proud of what we did. No one had done it before, not on this scale, and none that could produce as much as the one we built together. And against incredible odds, in one of the most difficult landscapes I’ve ever worked.”

Editor’s note: To make a donation to Father Rick Frechette’s charity, the St. Luke’s Foundation for Haiti, please visit this link. Any aquaculture or seafood businesses that wish to donate feed, equipment or other resources to the St. Damien Pediatric hospital, please contact the author.

Follow the Advocate on Twitter @GAA_Advocate

Now that you've reached the end of the article ...

… please consider supporting GSA’s mission to advance responsible seafood practices through education, advocacy and third-party assurances. The Advocate aims to document the evolution of responsible seafood practices and share the expansive knowledge of our vast network of contributors.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Author

-

James Wright

Editorial Manager

Global Aquaculture Alliance

Portsmouth, NH, USA[103,114,111,46,101,99,110,97,105,108,108,97,101,114,117,116,108,117,99,97,117,113,97,64,116,104,103,105,114,119,46,115,101,109,97,106]

Tagged With

Related Posts

Responsibility

An African prison where fish will be farmed and lives saved

A nonprofit organization working to improve conditions in African prisons is hoping tilapia ponds, tended to by inmates, will aid in their nutrition. A small donation from the Global Aquaculture Alliance will go a long way.

Innovation & Investment

Investing in Africa’s aquaculture future, part 1

What is the future that Africa wants? Views on how to grow aquaculture on the continent vary widely, but no one disputes the notion that food security, food safety, income generation and job creation all stand to benefit.

Innovation & Investment

Is Africa a ‘new Asia’ for aquaculture?

Now is the time for investment in efficiency improvements, better genetics, health management and more competition and innovation in the feed sector. Let's not perpetuate the myth that just a little more investment in some technical solutions will solve the problems in Africa.

Innovation & Investment

Caribbean producer aims to make a name for sutchi

Pangasius farmed in the Dominican Republic? True story. Value Aquaculture, with partners hailing from Germany and Chile, is trying to get U.S. buyers to take a fresh look at the Mekong catfish species.